In het eerste deel van dit tweeluik stond ik stil bij de opvallende explosie van consumentenkrediet in Brazilië gedurende het afgelopen decennium. Zwaar getraumatiseerd door horrorverhalen over subprime hypotheken, overkreditering, CDO’s en failliete banken, zijn we als beleggers tegenwoordig meteen op onze hoede als het woord ‘krediet’ valt. Komt de volgende kredietcrisis overwaaien uit Brazilië?

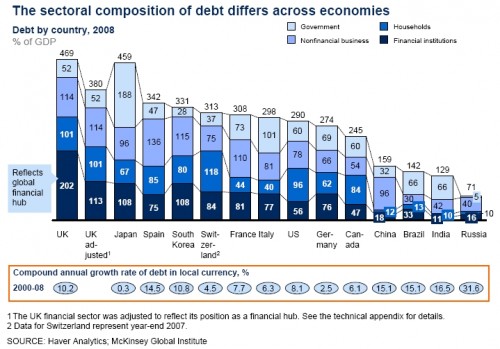

Wie weet. Maar laten we eerst even een paar zaken in perspectief plaatsen, in paniek raken kan daarna altijd nog. De Braziliaanse consument mag in de afgelopen jaren de credit card hebben omhelsd, nog altijd vormt household debt slechts een fractie van de totale schuld van het land. In zogenaamde ‘volwassen’ economieën, zoals de Verenigde Staten, Canada en Zwitserland, maken de schulden van huishoudens een veel groter deel uit van de totale schuld van het land:

Klik op grafiek om te vergroten (opent in nieuw venster)

Samenstelling van schuld per sector in 2008. Bron: McKinsey Global Institute

Uit dezelfde grafiek blijkt overigens ook, hoe het met de algehele schuldenlast van Brazilië (en andere BRIC-landen) gesteld is, afgezet tegen de westerse naties. Waar de schulden van Brazilië in 2008 uitkwamen op 142% van het GDP, maakten landen als Zwitserland, Japan, het Verenigd Koninkrijk en Frankrijk het veel bonter: zij lieten hun schulden oplopen tot meer dan 300% van GDP. Drowning in debts? Dat lijkt meer te gelden voor de westerse wereld dan voor de BRIC-landen, zoals ook de recente crisis in de eurozone pijnlijk duidelijk heeft gemaakt.

Is Brazilië dan het beloofde land voor beleggers? Dat mag u helemaal zelf bepalen. Brazilië is een land in opmars. Dat is geen garantie voor snelle rendementen. Niet voor niets waarschuwde Mark Mobius, emerging market goeroe bij Franklin Templeton, in een recent interview dat de BRIC-markten op korte termijn de nodige volatiliteit kunnen laten zien (hij bleef evenwel positief ten aanzien van de lange termijnperspectieven voor landen als China en Brazilië). We hoefden niet lang te wachten op een mooi voorbeeld van die volatiliteit: nadat in april het voorlopig hoogste punt van 2010 (circa 72.000 punten) werd bereikt, leverde de BOVESPA een slordige 10.000 punten in, met dank aan alle commotie in onze eigen regio.

Volatiliteit op de Braziliaanse aandelenbeurs zou ook kunnen ontstaan bij de presidentsverkiezingen die dit jaar zullen plaatsvinden. Of bij een verder oplopende rente. Want het kan ook té goed gaan met een land. Indrukwekkende groeicijfers zijn mooi, de gedachte aan een oververhitting van de economie houdt de Braziliaanse minister van Financiën ongetwijfeld vaak uit zijn slaap: het zou niet de eerste keer zijn dat Brazilië ten prooi valt aan (hyper-)inflatie. De basisrente (SELIC) in Brazilië werd in de periode volgend op het uitbreken van de kredietcrisis stap-voor-stap verlaagd tot 8,75%. Naar westerse maatstaven is dit nog steeds hoog; de Brazilianen waren allang blij dat de rente niet langer een getal van 2 cijfers vóór de komma was. De autoriteiten zijn nu van mening dat men de monetaire teugels lang genoeg heeft laten vieren. In april werd de rente al verhoogd tot 9,25% en een verdere stijging is niet onwaarschijnlijk. Deze week maakte een onderzoek van de Braziliaanse centrale bank duidelijk dat economen rekenen op een rentestand van 11,75% tegen het einde van 2010 (bron: Bloomberg).

Dit kan betekenen dat ook de rente die banken in rekening brengen bij hun debiteuren, opgeschroefd wordt. Mogelijk gevolg: consumenten die minder genegen zijn om zich in de schulden te steken. De vraag rijst, of dat nu een geruststellende of een teleurstellende gedachte is.

Allard Gunnink

Disclaimer

Allard Gunnink is als redacteur werkzaam voor de Beleggers Coöperatie, de beleggingssupermarkt van Nederland. Deze column is niet bedoeld als beleggingsadvies. De auteur kan posities hebben in (beleggingsinstrumenten op) onderliggende waarden die hij beschrijft.

6 gedachten over “Brazilië: carnaval en credit cards (2)”

Het staat buiten kijf dat Brazilie inderdaad een land in opmars is. En een land in opmars heeft, in tegenstelling tot een land in neergang, een positief economisch perspectief. Geld hebben ze wel in Brazilie, maar het is nu zaak om daar constructief mee om te gaan.

Inflatie, de grote angst van het land, wordt in Brazilie niet veroorzaakt door een stijging van de grondstofprijzen, ook betreft het geen zoals in veel westerse landen wel het geval is monetaire inflatie (bijprinten van geld) en het is ook geen wisselkoers inflatie, de Braziliaanse real was in de afgelopen jaren één van de sterkst stijgende munteenheden ter wereld. In Brazilie wordt de inflatie veroorzaakt door a) overmatige overheidsuitgaven (fiscale inflatie) en b) de klassieker; overbesteding met als gevolg bestedingsinflatie.

Wat de overheidsuitgaven betreft verwacht ik dat ongeacht de uitkomst van de verkiezingen in oktober deze zullen worden teruggebracht. Het vraagstuk van overbesteding is dan ook veel interessanter.

Overbesteding omschrijft de situatie waarin de vraag het aanbod overstijgt. Of anders gezegd het aanbod niet aan de vraag kan voldoen. Er wordt te veel geld uitgegeven voor te weinig goederen waardoor de prijzen zullen stijgen. Hierdoor ontstaat bestedingsinflatie wat het gevolg kan zijn van (overmatige) geldschepping in de vorm van kredieten door de geldscheppende banken. Want hoe kunnen mensen en bedrijven betalen voor de extra vraag die ze uitoefenen? Het lenen van geld vergroot de collectieve vraag en zal in een situatie van overbesteding, wanneer de productiecapaciteit nog niet is meegegroeid, leiden tot prijsstijging. Bedrijven zitten in zo’n situatie met een volledig bezette productiecapaciteit en hebben moeite om aan de vraag van hun klanten te voldoen.

Uit bovenstaande is dus op te maken dat in het geval van Brazilie de productiecapaciteit niet lineair meegroeit met de beschikbaarheid van geld. Allerlei oorzaken liggen hier aan ten grondslag, te weten; infrastructuur, bureaucratie, niveau van de publieke diensten, informele sector, mate van macro economische stabiliteit, etc. maar de primaire oorzaak is zoals altijd de arbeidsproductiviteit. Mc Kinsey rekende in 2007 al uit dat de arbeidproductiviteit van een Braziliaan gelijk staat aan 18% van dat van een Amerikaan. En daar zit mijns inziens het probleem. Om deel te kunnen nemen aan de wereldeconomie zal de Braziliaan zijn of haar arbeidsproductiviteit moeten verhogen.

Ik schreef zelf al eens (www.boudewijnrooseboom.nl) dat synergie, waarbij het geheel meer is dan de som der delen, in Brazilie welhaast tegenovergestelde effecten genereert. En dat is uitermate funest voor een oververhitte economie waarin de hoge vraag welliswaar tot een daling van de werkloosheid zal leiden, maar waarbij dit nieuwe personeel op termijn ook weer gaat besteden (vragen) met logischerwijs een prijsstijging tot gevolg. En als nu met deze personeelstoename de arbeidsproductiviteit per capita daalt, en dat doet zij sowieso wanneer bedrijven al te maken hebben met een volledig bezette productiecapaciteit, dan komt dat de oververhitte economie en daarmee het probleem van bestedingsinflatie niet ten goede. Scholing, efficiency, ondernemerschap, innovativiteit en noeste arbeid zijn dan de sleutelwoorden. Kom daar maar eens om in Brazilië.

Zeer interessante en lezenswaardige reactie!

En jawel:

http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE65A56D20100611

CHINA | BRAZIL

President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva praised this week’s gross domestic product data, calling it well-deserved “exuberant growth,” but some say such rampant expansion could be a curse, not a blessing.

Sound economic policies have made Brazil a magnet for investment but now Latin America’s largest economy is facing a collision with old problems: a chronic lack of infrastructure and human capital.

Brazil lacks the infrastructure and factory capacity to cope with these growth levels without fueling inflation, analysts say.

It also cannot match the massive and highly qualified work force and the amount of investment in infrastructure and capital goods that has allowed China to sustain double-digit growth rates.

“We have clear bottlenecks and our daily lives are evidence of this,” Roberto Padovani, chief Brazil strategist at WestLB in Sao Paulo, said. “It is difficult to find workers, you don’t have enough streets and highways, the airports are a mess.”

Investment, a gauge of corporate and public capital spending and inventory build-up, is currently at 18 percent of GDP, less than half China’s investment rate of around 40 percent, said Marcelo Carvalho, chief Brazil economist at Morgan Stanley in Sao Paulo.

And China invests around 16 percent of its GDP in infrastructure in contrast to only about 2 percent in Brazil, he said.

“If you don’t invest enough you are not expanding the supply side of the economy fast enough to cope with this booming demand. So when demand is growing faster than supply it spills over into pressures on inflation,” Carvalho said.

Brazil’s economy grew at its fastest pace in at least 14 years in the first quarter of 2010, up 9 percent on an annual basis. That was only moderately below China’s 11.9 percent growth rate in the same period.

The growth data gave another confidence boost to a government facing a tight election race against opposition party PSDB in October. Lula spoke of a “golden age” for Brazil, and Central Bank President Henrique Meirelles said it proved the government’s anti-crisis strategy was right on the money.

But for others, Brazil’s buoyant growth raises a red flag: inflation.

BLESSING VS CURSE

Economists say Brazil can only grow between 4 percent and 5 percent before growth starts fueling inflation and hurting the current account, the widest measure of a country’s foreign exchange transactions.

With the economy expected to expand between 6 percent and 8 percent this year, it is clearly growing above potential.

In a sign that Brazil’s resources are being stretched thin, unemployment dropped in April to its lowest rate for that month since 2002, when the government began tracking the data.

And the combination of strains in supply and red-hot demand resulted in growth of imports outstripping that of exports, widening the current account deficit.

The use of installed factory capacity also reached pre-crisis levels in April as Brazilian manufacturers pushed equipment and personnel to produce more.

“Current output is about 1.7 percent above potential, confirming that the output gap is now negative, and that means that inflationary pressures are mounting,” Standard Chartered said in a note published on Thursday.

Headline inflation slowed in May, but underlying price pressures remain strong.

Core inflation, which strips out the prices of food and other volatile goods, jumped to 0.59 percent from 0.45 percent in the previous month, and 12-month inflation at 5.22 percent remains well above 4.5 percent, the center of the government target.

Inflation is also accelerating in the services sector, which makes up about two-thirds of Brazil’s economy, according to Carvalho. Prices in the sector grew around 0.6 percent in May from a 0.5 percent rate in April and surged 6.78 percent year-on-year in May, he said.

The government has taken steps to curb pricing pressures, announcing additional cuts to the 2010 budget, while the central bank has increased interest rates by 150 basis points since April to 10.25 percent.

Brazil’s finance minister, Guido Mantega, expects those hikes, along with the phase-out of government tax breaks and the euro zone debt crisis will help cool growth in coming quarters.

But if underlying price pressures show anything it’s that monetary authorities still have work to do.

“Inflation numbers in services are a closer reflection of the domestic economy than overall inflation numbers are, and services are running above target,” Carvalho added.

“It means there are inflation pressures that have to be dealt with. It means that the central bank’s monetary tightening job is not over yet.”

(Editing by Leslie Adler)

Ik ben benieuwd hoe de rente in Brasil zich zal ontwikkelen in de komende maanden!

Brazil inflation is down but not out

POSTED ON JULY 9, 2012 · ADD COMMENT

By Mary Stokes.

Annual inflation has trended steadily downwards since peaking at 7.3% in September 2011. Given sluggish domestic economic activity and weak global growth, price pressures are not a concern, at least not in the near-term. Analysts now see inflation slowing to 4.9% in 2012, according to the latest central bank survey, compared with expectations of 5.4% at the start of the year. Nevertheless, we do not expect this decline to prove lasting.

What is surprising is that inflation is not lower. Global commodity prices fell by 7.2% annually in May, according to IMF data, while GDP growth registered its weakest annual reading in ten quarters in Q1 2012. Despite these disinflationary developments, annual inflation remains above the mid-point of the central bank’s target range of 2.5% to 6.5% (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Inflation and the SELIC rate have fallen since 2011

Source: Timetric

This should serve as a warning signal to policymakers who want a lasting reduction in the SELIC rate. Even though the SELIC currently stands at an all-time low of 8.5% with further cuts expected, Brazil’s policy rate remains higher than those in most other emerging markets. The danger is that when growth picks up, inflation will follow suit, making it challenging for the central bank to keep the SELIC rate at the current, low levels.

So why is inflation above target in the current disinflationary environment? The short answer is the labour market. Despite weak growth, the unemployment rate is close to a decade-low and wage pressure is visible in the divergence in inflation between tradables and non-tradables. The non-tradables sector consists largely of services, which cannot be readily exported or imported. In May, prices for non-tradables rose by 7.5% annually, compared with just 3.5% for tradables.

Part of the issue is cyclical. The unemployment rate tends to be a lagging indicator. Given weak economic activity, we expect a modest increase in unemployment in the coming months, which may help ease wage pressure.

However, part of the issue is structural, which has prevented a more significant slowdown in inflation. For example, Brazil suffers from a shortage of skilled labour – a structural issue related to the government’s historic under-investment in education. According to Manpower’s 2012 Talent Shortage Survey, Brazil ranked second, behind only Japan, with 71% of employers reporting difficulties filling jobs. This has contributed to inflationary wage increases.

The government’s minimum wage policy is also a structural stumbling block to lower inflation. The policy, enshrined into law in February 2011 but de facto adopted in 2007, helps perpetuate inflation by ensuring minimum wage hikes consistently outpace rises in consumer prices when the economy is growing. One of the main problems is that the minimum wage is determined by a backward-looking formula based on real GDP growth two years prior.

If the government were to peg rises in the minimum wage to rises in labour productivity and consumer prices, rather than rises in overall GDP growth from two years prior and consumer prices, this would help limit inflationary pressures. Most importantly, it would bring the government closer to achieving its goal of a lasting reduction in interest rates.

Weet je wie er pas een schuld heeft? Amerika, en dan vooral aan de studentenleningen kant, en bovendien vergeet de opgebouwde schuld van het land niet niet die nu al ruimschoots boven die van 1929 zit. Een volgende kredietcrisis, of hoe je het ook wilt noemen, zal niet uit de hoek van Brazilië komen, hoe ‘slecht’ het er daar ook voor staat.